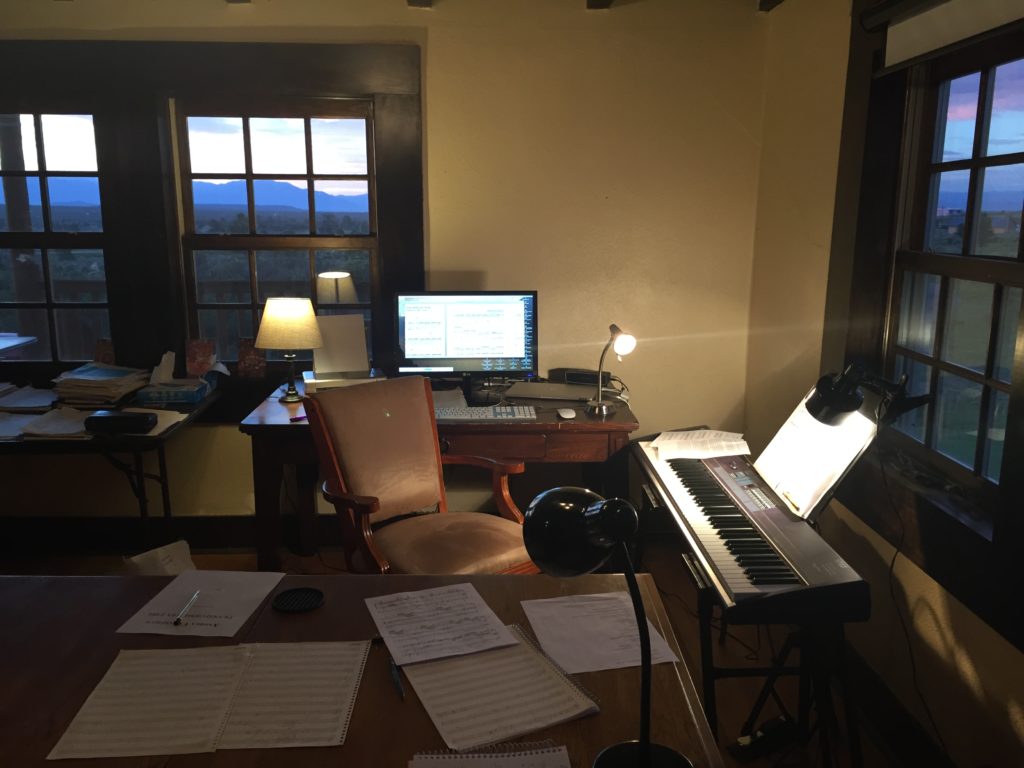

“Mi Casita,” Aldo and Estella Leopold’s home in Tres Piedras, NM, now the site of the Leopold Residency Program. Photo courtesy of Andrea Clearfield.

Conservationist, forester, philosopher, educator, writer, and outdoor enthusiast Aldo Leopold (1887-1948) is considered the father of wildlife ecology. Leopold underwent a transformation in his perspective on wildlife through a life spent in engagement with the natural world. Leopold writes of one such pivotal moment in essay “Thinking Like a Mountain,” in which he and his friends shot at a mother wolf and her pups:

“We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes – something known only to her and to the mountain. I was young then, and full of trigger-itch; I thought that because fewer wolves meant more deer, that no wolves would mean hunters’ paradise. But after seeing the green fire die, I sensed that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view.”

Leopold would come to understand wolves’ crucial role in the health of ecosystems, which was proven by the successful reintroduction of wolves into Yellowstone National Park decades after Leopold’s time. (Justin Ralls explored this topic in an essay and composition for Cadillac Moon Ensemble, Of Wolves and Rivers, for Landscape Music’s National Parks centennial concert last year.)

Andrea Clearfield, left, and Ariana Kramer, right. Photo courtesy of Andrea Clearfield.

Leopold’s legacy lives on through the Aldo and Estella Leopold Residency Program: a monthlong retreat at the Leopolds’ first home in northern New Mexico, owned by Carson National Forest and hosted by the Leopold Writing Program. This past August, the residency program—usually reserved for environmental writers—hosted an unusual project: Transformed by Fire, a collaboration between renowned Philadelphia-based composer Andrea Clearfield and poet and freelance writer Ariana Kramer from Taos, NM. Their song cycle for baritone and chorus takes Leopold’s writings as a jumping-off point for a musical and poetic exploration of wolves and their role in our ecosystems.

Last June, prior to their residency and the subsequent concert performance of their work-in-progress, I sat down with Andrea and Ariana in Taos to discuss the origins and goals of Transformed by Fire. The following excerpts from this interview offer a snapshot of the formative, early stages of their collaboration—a glimpse into their creative process.

Andrea Clearfield and Ariana Kramer. Photo courtesy of Andrea Clearfield.

The genesis of a collaboration

Ariana Kramer: I interviewed Andrea for an article in The Taos News when she was performing some music with the Taos Chamber Music Group. I went to her concert and we connected, went for a hike together, and just really hit it off. I shared with her some of my poetry. Then I found out about the Leopold Writing Program residency and thought immediately of Andrea.

Andrea Clearfield: I found out about the Leopold residency separately! So it’s funny, we were both thinking about it. It’s been a writer’s residency and I didn’t know if they accepted composers. I had met someone who works for the Leopold Foundation through you [Ariana] and emailed him: “would you consider a composer and writer collaboration?”

Kramer: I have a background in biology, ecology, so that’s always been an interest of mine. It feels like what came together between us was very organic. The story of Leopold’s encounter with the wolf was something that had always struck me. So, when we were initially thinking about a collaboration I immediately went to that story and the video about wolves in Yellowstone.

Clearfield: The poems that you [Ariana] gave me before I left my last residency [at the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation of New Mexico in Taos] really stayed with me…there was something about transformation and your relationship with the natural world and how it soared in your work. So I immediately thought that I could write music to your words and we could come up with something together.

I’ve always been drawn to the natural world. I do a lot of residencies because the environment feeds me; the natural beauty and the ways that I can respond through music—not just melody and rhythm, but vibration. Recently I’ve been doing more collaborations, working with filmmakers and artists on-site…So, when this opportunity came up to respond to Leopold, and particularly your idea about the transformation in his character through this experience that he documented much later in his life, I responded both from the point of view of: this would be so amazing to be out there and create the work in the place that he built, where his ideas were becoming manifest, and: what is possible in human beings to transform themselves? As I am currently writing an opera, this is what I’m thinking about. The transformation of the main character that opens up into something entirely different from what he was at the beginning. That had been on my front burner. So all the pieces came together.

Kramer: I think it was the last night you were here for your [Wurlitzer Foundation] residency—I came over to your casita, and you played me some of the music that you had been working on with [a collaborator based in Santa Fe]. It really struck me and I think it initiated a conversation with you about endangered species, particularly, and about doing some kind of creative work like an installation piece that would have a focus on endangered animals. That was already an idea we had talked about before we heard about the residency. So that’s what I mean when I say it happened organically.

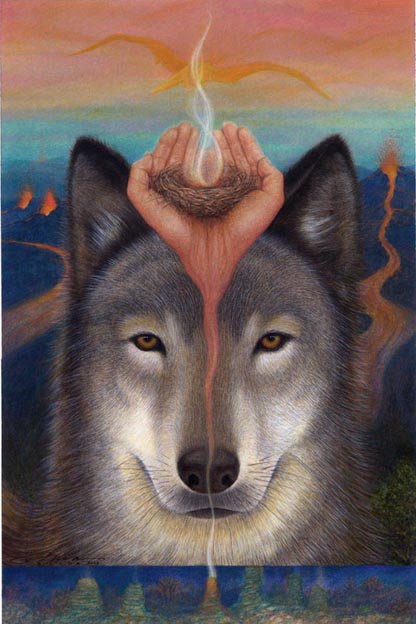

“Gray Wolf II” by dalliedee. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Finding poetry in ecology

Kramer: I’ve been reading a lot of material that is more technical than poetic. Reading excerpts of Aldo Leopold’s game management textbook and pieces that he and others have written that are more dense, scientific, academic material. My background is helping me to understand it and put the pieces together. I was drawn to study biology and ecology because I had a strong connection to the natural world. My study of the natural sciences helped me to see and understand more about the complexities of plants, of animals, of their interactions, and just deepen in my appreciation for what they are. And at the same time, it also let me see how science can objectify and create “the other.”

So it’s interesting actually trying to get into Aldo Leopold’s thinking, trying to understand him in his entirety of who he was, as someone who was a forester, who started the field of wildlife ecology, who started game management, and who was a hunter. Hunting was an important part of his life, all his life. So he’s a very complex person, and I feel like my science background is helping me to understand some of the different lenses through he which he lived his life and did his work.

“Estella and Aldo Leopold” by USFS Region 5. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Clearfield: [The idea of including a narrator in Transformed by Fire] came up to provide background and educate people about the story behind the story, and his life, for people who are not as familiar with Leopold’s life and legacy. For me, I think it raises musical challenges. And I wasn’t quite sure if it was going to work. So I would like to try to find a way to have the more prose-like sections either sung or implied or, if there’s going to be some sort of pre-recorded sound, there might be some other way to deliver that. We discussed possibly the narrator might take people out of the experience and music and poetry world that we want to create.

Kramer: One of my challenges as a writer is in wanting to talk about the ecology of the wolf in a language that is poetic when the resources that I’m drawing on are not poetic and there’s a lot of language in my head that doesn’t necessarily sound great.

I read “Among Wolves” written by Marybeth Holleman and Gordon Haber about a long-term study by Haber on wolves in Alaska. I’m weaving into poetry what I learned from reading that book about what wolves are, how they function, and how they are so close-knit—they’re even more close-knit as a family than humans, in terms of their social bonds. I’m also learning that there’s an alpha pair in a wolf family and the female is actually the one that’s the leader of the group. Aldo Leopold, when he had his encounter, it was with a mother wolf and her yearlings. So I’m referencing the wolf he encountered as a “she,” and I continue to reference the wolf as a “she” throughout the piece, even though I am speaking about wolves in general. I do this to highlight the fact that the wolf is an animal that has a female at the forefront of their family group.

Yesterday, I shared with Andrea for the first time some of what I’ve been working on. So that was a big step.

At work on Transformed by Fire at the Leopold residency in August 2017. Photo courtesy of Andrea Clearfield.

A musical response

Clearfield: It was a really special time yesterday to be able to see what [Ariana is] writing. And it’s so fresh, and it’s not finished, and it’s not how she usually works to show her drafts in progress, but I told her that’s how I like to work with a writer, so that a lot of material might be generated. I like even to see the drafts so choices can be made for the music; some words and phrases might sit better in the voice than others. And to see how Ariana is crafting this in a series of ten movements through different kind of metaphors and archetypal themes. The theme of separateness into togetherness and interconnectedness, or the theme of youth into maturity and some kind of wisdom or larger perspective. The perspective of family and comparing and contrasting the wolf family to the human family, Leopold’s family. And how she will go from giving us insights into the story, the description of what happened, and then move into a place of poetic rendering of it that feels really personal to me. So I was very excited by that. We also discussed the architecture, overarching form and building blocks (recurring words, motives, rhythms, or themes) of the piece and how they could transform over time.

This is a very unusual situation for me. I’m working primarily as a composer and working on different commissions with their own timelines. And this is a residency that has as part of the residency the development of a new project, which is different than the other residencies I’ve held where I come in with a project. My work can take quite a long time to develop, so Ariana was okay with the idea that perhaps only some of the poems would be set to music. No matter what happens, it’s the process and not necessarily the finished product that is important here. And I find that very liberating actually; there isn’t a deadline at the end of one month to have a finished cycle, which feels like it wants to be bigger than what the time may actually allow.

I told Ariana yesterday that when I get to the cabin, sit at the piano, and start to sing the words, the whole experience will actually inform how this piece is going to be shaped and what it is going to be shaped for. [My starting point is] baritone, horn, and piano. If I start to hear string quartet, or electronic sounds, or field recordings, [I might bring that] into the piece.

Artwork by Mia Bosna. Courtesy of the artist.

Communicating with music

Kramer: Especially at this time, politically, I’ve been thinking a lot about—and I’ve talked to Andrea about this—not wanting to step into the politics of wolves, which is almost impossible. But lately I’ve been thinking about how important it is to emotionally bolster those people who are advocating for the wild, for the wilderness, in whatever way they’re doing that. And I’m trying to keep that as my focus as I’m working on this piece. There are so many places that you could go politically with wolves, so easily, and I think I’m really trying to create a heartfelt experience for people. So that wherever they are—if they’re hunters, like Aldo Leopold was, if they’re vegan, wherever they stand on the spectrum in terms of their relationship with animals, they can connect with the piece. I think ultimately what Aldo Leopold was calling for was that we have a greater connection with the natural world and that we understand that we’re part of it and that we belong to this great whole. And that’s what I’m hoping to communicate through this piece.

Clearfield: Echoing what you said about the heartfelt experience, I think if there is a musical poetic experience—a world that we’re inviting people into—and they step through that door, and they feel something, that’s already the beginning of it. That they have their own experience. So I think we’re pretty much in agreement on that, that this is a portal into shedding light on the spirit of the animal and the relationship, the interdependence. For me that’s such a healing aspect. And that’s what I’d really like people to take away.

…another element of my work is documenting Tibetan melodies in the Himalayas. Through that documentation, I’ve created musical responses. And the outcome of that has been more of an engagement with a Himalayan preservation initiative to help document an endangered language, because people are leaving and things are changing in the village…I’m finding that performances of the pieces or talks that I’m giving about the pieces can help educate people about an endangered culture and language and that they might want to take their own initiative after having attended that concert or lecture and perhaps support it in some way.

So, I think there are possibilities for future engagement. If people are receptive and something stirs their soul, there might be somebody out there who gets a big “Yes, wow, I really want to go in and find a way that I can support the Leopold Foundation or the endangered species.” So, for me, that belief has been strengthened in the power of music and arts to have this capability to connect, transform, and create positive change.

Kramer: One thing I admire about Aldo Leopold is that in writing his land ethic, he didn’t give a set a rules. He left things very open for people to interpret for themselves. This is an example of how he wrote—I think this really sums up Aldo Leopold’s land ethic:

“A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

Andrea Clearfield, pianist, rehearses with Mark Jackson, baritone, and members of the Taos Community Chorus at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, NM. Photo courtesy of Andrea Clearfield.

After the residency

On August 30, 2017, following their Leopold Writing Program residency, Andrea Clearfield and Ariana Kramer gave a workshop presentation of Transformed by Fire at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, New Mexico. Five movements of music were performed by Clearfield, a pianist, and sung by baritone Mark Jackson with members of the Taos Community Chorus. A repeat performance was held on September 6 in response to popular demand.

At the time of this writing, Kramer has written the draft for a full ten-movement libretto, of which the five-movement song cycle presented in August was an excerpt. Clearfield composed these five movements during her monthlong residency in Leopold’s cabin. The composer described finding inspiration in Kramer’s thoughtful and evocative poetry, Leopold’s essays and letters, and her experience of living in the cabin where she was close to the natural world Leopold had experienced just over a hundred years earlier.

Clearfield and Kramer actually rehearsed the music with baritone Mark Jackson several times inside Leopold’s own “Mi Casita.” For the Harwood Museum workshop presentation, Clearfield also added a part for “pop up” chorus, seated throughout the audience, to create an immersive and intimate environment through which to convey the ending message of the work expressed in Kramer’s libretto: “everything on, over, and in the land belongs together.” Clearfield imagines this work expanding into an evening-length cantata for baritone, chorus, and large chamber ensemble, which may also include staging, visual projection, and dance theater. The two collaborators are currently seeking funding to complete their project.

Andrea Clearfield is an award-winning composer of music for orchestra, chorus, chamber ensemble, dance and multimedia collaborations. Learn more at her website.

Ariana Kramer has a background in writing, biology and education. She recently published poems with “The Poetry Box” and “Taos Journal of International Poetry and Art” and is currently working on her first poetry manuscript.