Editor’s Note: Composer Christina Rusnak writes her fourth essay for LandscapeMusic.org.

Last October, Nell Shaw Cohen, Stephen Wood and I met to discuss the feasibility of a developing a concert series to celebrate the 50th Anniversaries of the Wild and Scenic Rivers and National Trails System. Eleven months later, concerts are premiering in Vallejo, CA (9/23); Atlanta, GA (9/29); Houghton, MI (10/4); Portland, OR (10/7); and Boston, MA (11/3), as part of Landscape Music: Rivers & Trails concert series. My music is being performed in all locations except Boston. Determining what river or trail I would write about was easy—2018 also marks the 175th anniversary of the Oregon National Historic Trail, and I live just 12 miles from the trail’s end.

The Oregon Trail, and our near-mythological familiarity of it, is fraught with controversy. Claimed by both the British and Americans, the land was actually controlled by the indigenous inhabitants who had no idea what was coming. The emigrants who traveled the 2,170 mile Oregon Trail began their journey in Independence, Missouri—skirting the northeastern edge of what is now Kansas and traveling through Nebraska, Wyoming, and Idaho into Oregon, although none of these states actually existed until decades later. The hopeful settlers traveled through “Unorganized Territory” into Oregon Territory. While most people dispersed along the way to settle within east or south of Oregon Territory, the route officially ended at Willamette Falls—the second largest waterfall (in the U.S) after Niagara. About 20% of emigrants, over 80,000, followed the trail to the end.

How could I possibly capture all of the trail’s glories and tragedies in one musical work? I couldn’t. So, my compositional approach focused on unearthing the mostly undocumented history of the trail, and fusing it with well-known facts about the emigrant experience. In other words, I took the controversy head on. The Oregon Trail was not “discovered” or created by European explorers. The Trail connects wildlife and indigenous trading routes that have existed for thousands of years. The iconic sites, made famous by the settlers with memorable names and carved graffiti, were already important landmarks for tens of centuries.

Since the Trail is generally divided into three segments—the Plains, the Mountains and Oregon (which actually starts in southwestern Idaho)—I decided to choose three sites, one from each portion along the trail, and create a movement for each site using the indigenous place names. But which ones? And how could I find out their indigenous names? Familiar with the environmental and cultural history of the last section of the trail, I traveled to Nebraska and Wyoming in July following the trail closely along state highways and backroads. The current visibility of the wagon ruts attests to the sheer numbers of people imprinting their journey into the soil.

Scott’s Bluff National Monument. Photo © 2018 Christina Rusnak.

Exploring the plains of western Nebraska, I hiked along the top and back of Scotts Bluff. While contemporary life surrounds the National Monument, a portion of the surrounding prairie has been restored to resemble how the emigrants would have traversed it in the 19th century. National Park personnel told me how Scott’s Bluff, Me-a-pa-te, was much more important to Native Americans than the more striking Chimney Rock a few miles before (east).

South Pass Wyoming, WyoHistory.org, Photo by Terry Del Bene, 2014.

In the mountains of Wyoming, I met with John Washakie, the great-great grandson of the legendary Chief Washakie, at the Shoshone Cultural Center. When I explained my mission, he told me that the South Pass, Mudza, was the most important site in the mountain region for indigenous people. For emigrants, the South Pass, which crosses the continental divide, marked the halfway point of the trail. Choosing the site for my last movement was obvious: Willamette Falls, Hyas Tyee Təmwata.

Musically, I attempt to take the listener back to the landscape itself and to life prior to and during the pioneers’ cross-country experience. I sought to honor the precolonial past of the landscape and its historical inhabitants and fuse that with the experience of the settlers. Me-a-pa-te (Scott’s Bluff) translates as “hill that is hard to go around.” The surrounding Platte River Valley served as a pathway, hunting area, and farmlands for thousands of years. The music interweaves the prairie landscape, the sound of the hunt, and the rhythm of the wagon wheels as they travel by the bluff.

Mudza served as a primary corridor and conduit of continental trade for millenia. The South Pass served as the essential point in Western geography and history for the American vision of Manifest Destiny. The pass is so wide and gradual that most settlers couldn’t tell when they crossed it. Musically, I use long notes and a wide spectrum of frequencies to reflect the landscape.

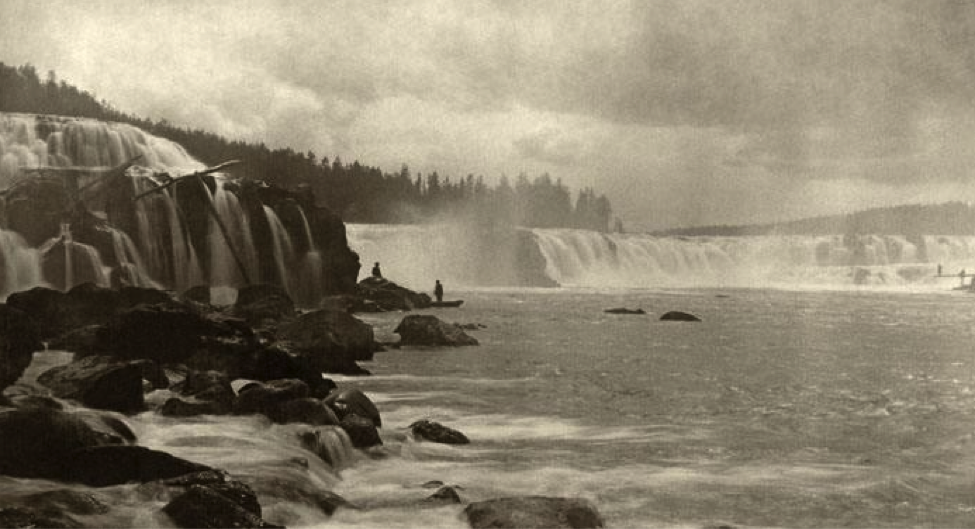

Courtesy of Clackamas County Arts Alliance, OR.

Fur traders, writers, and painters had built up the Oregon landscape as Eden in the American imagination. Prior to the American migration, Hyas Tyee Təmwata flourished as a major fishery, with a thriving society of people living in semi-permanent villages. The third movement ties together the falls: the traditional importance of this place and the excitement of the setters upon their arrival.

Some aspects of composing this piece surprised me. While my original intent was to feature the landscapes that were important both to the indigenous people living along the trail and to the settlers traversing the trail itself, the conflicting emotions of these people, and perhaps even of myself, found their way into the music.

LEARN MORE

Dozens of sources exist: These are but a few. I consulted with the University of Wyoming, which is working on a project to identify and catalog all the indigenous place names in the state.

National Park Service: Oregon National Historic Trail

Oregon Encyclopedia: Willamette Falls

Wyoming History: Mountain Shoshone

Trails Across Wyoming